Quadrifoglio – An Old Alfa Never Dies (1986)

Richard Banks, an Alfa specialist, forecasts a bright future for the Giulia Sprint. Richard is the man knowledgeable aficionados go to in England for top-class post-war models, Giulias in particular. Not that you would guess from his premises. The stockroom is an old cow-shed; the display area, a gravelled courtyard; his restoration workshop, the back room, once the village shop of a 15th Century thatched house in Wickhambrook, deep in rural Suffolk.

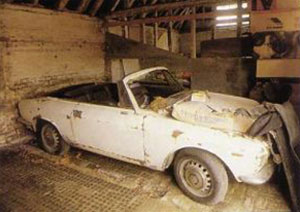

‘All I do here is pull the strings. I take the cars apart and re-assemble them afterwards. The specialist’s work, I farm out to local experts.’ We were admiring Richard’s latest project, a rare right-handed GTC Cabriolet, over a pint of best bitter at the Cloak public house, a stone’s throw from what he describes as his cottage business. ‘People tend to under-value Alfas. Right now, I think the Giulia GT is the best-buy car of the Sixties. They’re crackers to drive…marvelous road cars. When all the wrecks have gone and only good ones remain, they’re bound to appreciate.

According to the oracle, Luigi Fusi, Carrozzeria Touring converted just 1000 Giulia Sprint GT’s to ragtop GTC’s, all of them 1600’s, in 1965-66. The Fixedhead Sprint, launched in September 1963, was penned by the maestro, Giugiaro, who was in his early twenties when he headed Bertone’s styling studio. ‘It was his thirteenth car design,’ recalls Richard Banks, who sees the Sprint as an enduring classic. ‘The GTC was the last car Touring did before they folded. They simply cut the roof off, reinforced the chassis, fitted a hood and made good the interior.

‘Of the 99 right-hand drive GTC’s Touring made, 75 came to Britain.’ Richard Banks, who keeps all these statistics in his head, prefers the lines of the Cabriolet to those of the Fixedhead. Its longer rear deck and deeper trunk lid gives it even better proportions, he thinks. Otherwise, the skin panels are the same.

Richard’s GTC, awaiting delivery to an English collector when we went to inspect the finished work, was one of the earliest, chassis number three. ‘When I first saw the car advertised for sale in an English Sunday newspaper five years ago, I couldn’t afford £3000 (($4200) asking price,’ Richard recalls. ‘Two years later, it was up for sale again in Scotland. I paid £1650 (about $2300) to a dealer, which I thought was fair for an original-condition GTC.’

Although the car had still done only 38,000 miles, it was actually in very poor condition, bodily and mechanically. ‘The body was a lot worse than it initially looked, really quite disgusting in fact,’ recalls Richard.

Stage one in the renovation program was to strip the car right down. Everything came off, including the brake and fuel lines, leaving only the wiring loom intact. ‘I folded that into convenient cavities,’ says Richard, who works solo at his lovely country home, surrounded by great sculptured yews, hundreds of years old. Hard graft with a liquid stripper and scraper knife removed all the top-surface paint. ‘We got as much off as possible so we could see the state of the metal beneath. Up to three applications were needed where the paint was really thick.’

Richard also dug out some minor crash-damage filler, but not Touring’s ample leading. Factory applied sealant on the underside was also left in place, as there was no need to attack good metal. The stress-bearing parts of the monocoque were not too corroded but the outer panels and boot were in particularly bad shape.

Richard was concerned that the GTC’s structural rigidity should not be impaired. Not that it was ever particularly god. After-market factory strengthening kits, including additional oversills (to give the original ones greater depth) and a cross-bracing square-tube structure ahead of the radiator, never completely eliminated scuttle shake.

‘The original sills were simply not deep enough to give the car the rigidity it needs,’ says Richard. ‘Jack the car up and the doors probably won’t open. Still, it’s nicer than it might have been without these additions.’

Bodywork repairs were done by Ken Godfrey, at his workshop in nearby Ramsey Heights, Cambridgeshire. ‘Super bloke – and very clever,’ enthuses Richard Banks.

‘He’s just built an aluminium body for a Maserati 150S sports racer, using only photographs as a guide.’

Ken’s first task was to evaluate the extent of the corrosion problem. ‘Italian auto bodies tend to be worse than others,’ he confides. After marking up the offending areas he cut them out by the most convenient means – usually an air chisel, though snippers and saws were also used. The worst rust was in the foot wells, trunk, spare-wheel well and inner wheel arches. ‘The trunk floor was totally gone. Ken had to remake it completely,’ says Richard.

Working on one side at a time (so he could use the other side as a pattern), Ken cut and hand-hammered into shape new panels. ‘The rear wheel arches were remade from the waistline down,’ he recalls.

New-for-old metal was also used to make good the door skins, corroded at the bottom and around the door handles.

Working from the inside out, Ken patched in his new panels with a continuous oxy-acetylene butt weld, hammering the joins into shape as he went. Only in the invisible floor and sill areas was the metal over-lapped and gas welded on both sides to give it additional strength.

The sills, front and rear panels and front fenders were replaced by Alfa Romeo pressings that Richard had in stock. And just as well, too, as Giulia Sprint body spares are now very scarce. The factory’s overnight decision to stop making them, bit hard and very quickly, it seems. ‘Everyone was shattered. Alfa’s best post-war classic and they don’t do body spares for it any longer. It’s a big problem,’ says Richard, who hopes that the press dies will eventually be brought into use again by someone else, perhaps by the Milan based spares retailer, A.F.R.A.

It was also Ken Godfrey’s job to ensure that the shut lines around the doors, hood and trunk were millimeter perfect. That meant careful juggling with the various panels before welding them into place. Finally, he ‘finished’ the whole body, smoothing it down with a rotary sander, ready for final paint preparation.

The rebuilt body-chassis unit, now bereft of iron oxide, was next trailed to another local expert, Neil Cawthorn in March, Cambridgeshire, for painting. Neil’s first task was to sand blast those parts of the body that couldn’t be reached with a rotary sander. Any depressions or weld pits were then lead filled and filed smooth. The next step was to treat the bare-metal shell with liquid cleanser, to remove all grease and sweaty finger marks. Then came a coating of self-etching primer which eats into the metal for half an hour, giving it a water-resistant surface. Alfa’s own primer was water based, and very vulnerable when a broken surface skin exposed it.

After three under-coats, the ‘surfacer’ as Neil calls it, the body was lightly flattened by hand in readiness for three top coats of low-baked German Glasurit gloss. Neil Cawthorne is scornful of the 20-coat paint jobs you read about in the car magazines. ‘I don’t like a car to look heavy with paint,’ he says. ‘It masks the body’s sharp edges and chips very easily.’ The lustrous, smooth sheen of the GTC’s paintwork indicates that a total of seven coats is just about right. Even that is 30 percent more paint than Alfa applied in the first place.

Like the body, the engine was in poor shape.

‘Normally, these 1600’s are good for 130,000 miles,’ said Richard, though they do tend to need head-off attention at perhaps half that distance. ‘The valve guides are the first things to go.’ The engine rebuild was entrusted to Bob Dove, a foreign currency expert at a London City clearing bank. Car and engine preparation is a spare-time relaxation for Bob at his Forest Gate workshop in Essex. ‘He does it for pleasure – and he does it brilliantly, better than a professional,’ says Richard Banks.

When the partially seized engine was stripped right down, Bob found evidence of previous inept attention (Helicoil inserts were needed to repair stripped-thread stud holes), as well as neglect. ‘It was more a case of reclamation than rebuild,’ he recalls. ‘The rusted bores and bearings suggest previous head-gasket trouble, which allowed water into the engine.’

Despite the poor state of the power unit, Bob retained as many original parts as possible. New pistons, rings and liners were fitted, all readily available as off-the-shelf spares. He also fitted new timing chains and replaced the bearings. The con rods, camshafts and crankshaft were kept. So was the block and head – equipped with new valves, guides and seats, of course.

Bob also had to strip and rebuild the Weber carburettors, fitting new gaskets, seals and ball races. ‘You wouldn’t normally expect an engine to be this bad,’ he says. Bob Dove, who has stripped and rebuilt many Alfa engines, is as enthusiastic about them as Richard Banks. But he warns that the need proper maintenance and gentle warming from cold, just like other quality light-allow engines, to avoid premature wear. As third gear tended to jump out of mesh, Richard also had the gearbox refitted by another of his local specialists. Unlike bodywork spares, those for the drivetrain are no problem. ‘They’re the same as the current 1600 and 2000 Spiders,’ says Richard.

Suspension work and re-assembly was done back at base by Richard himself, working within the old lathe-and-plaster walls of his Jacobean house, appropriately named Commerce House. ‘They used to sell everything here, from cloth to cabbages,’ he recalls.

The GTC’s original Dunlop brakes, along with the uprights, stub axles and larger discs, were replaced by alternative ATE ones from a later Alfa. Spares for the Dunlop system are difficult to get, says Richard. Besides, the ATE brakes are better. Richard also replaced the rubber bushes of the wishbone pickups, and fitted new dampers, coil springs and final drive.

Assembly was a straight-forward job, even though none of the bits and pieces were labeled during dismantling. ‘Everything was thrown into a big box. With a bit of experience, you can look at a bolt and know exactly where it goes,’ says Richard. During assembly, he applied rust preventative to anything that looked vulnerable. ‘I used a garden syringe and squirted it into every nook and cranny. Later on, the body received a proper professionally-applied application of rust proofing. The wheelarches were also liberally undersealed

Next stop, the trimmers, G & G Sergent at Felthorpe, Norfolk. Geoff Sergent was once in charge of the development trim shop at Lotus after learning the trade at Robinson’s, Norwich-based coachbuilders. Now he works with his son Gary in what was once a farmyard pig sty in a one-street village near the county town of Norwich. Word-of-mouth reputation brings many classy cars to their workshop. Following the GTC came a Rolls-Royce 20/25, Maserati Mistrale, Jaguar E-type roadster, MK 2 Jaguar and an AC Cobra.

Gary Sergent could recall no special problems with the GTC. ‘It was a fairly straightforward job that took us the best part of 10 days to complete,’ he says. The GTC started out with brown trim for its blue outer coat, but the new red livery dictated a change to black. ‘Alfa never mixed their colors,’ Richard Banks told us. As leather was used originally only on the 2.6 Sprint, the Sergents stuck to good-quality PVC for the GTC’s seats and doors.

Their first task was to remove the old material and make good any tired foam padding beneath. The new covers were then tailored to fit from their own measurements and stitched up on an industrial sewing machine.

As replacemtn GTC carpets are no longer available, new ones, with stitch-bound edges, were made up from a rubber-backed carpet originally designed for the MK 2 Jaguar. Black German mohair, as used by Mercedes-Benz and Rolls-Royce, went into the easy-fold hood (the trickiest part of the operation) and hood bag. ‘It’s all been done to the highest standards,’ said Richard, admiring the taut, crinkle-free top.

With its new stainless-steel bumpers, the finished GTC certainly does look immaculate. Just to complete the job, Richard also fitted new door handles (the old castings were badly pimpled), new front and rear lights, and a re-chromed hood finisher.

Around 500 man-hours went into the GTC rebuild. ‘It’s not been restored so much as renovated,’ says Richard Banks. ‘The secret of keeping the time and costs down is to know where you can cut corners without compromising quality. That only comes with experience.’ Total expenditure, which includes the GTC’s purchase price, was under £8000 – $11,500.